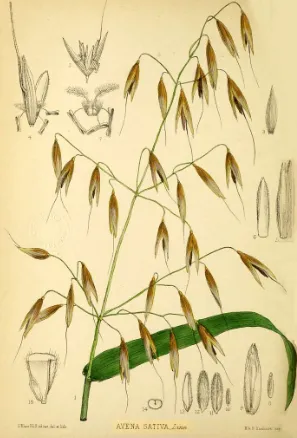

Phytates are a compound found mostly in unrefined grains (aka wholegrains). To get it out of the way - yes, phytates can inhibit the absorption of minerals such as iron. This happens as phytates bind strongly (called chelating) with iron or other minerals, preventing our bodies from accessing them. But, before you get scared and never eat a wholegrain again! Does this mean we should be avoiding phytate containing foods and be concerned about the effect they are having on us? The answer is no, not really - please let me explain why…

Although single meal studies have observed an inhibitory effect of phytates on the absorption of minerals such as iron and zinc, research looking at diets over a period of several weeks show less of an inhibitory effect. How can these contradictory results be?

In single meal studies, participants are fed a meal and then the effect of that single meal is studied, and the rest of the participant’s lifestyle or diet is not considered. While useful in research, these kind of studies aren’t totally comparable to an actual diet that a person eats. Single meal studies may therefore overestimate the inhibitory effect of phytates (Piskin et al, 2022). Research that looks at the effect of phytate in diets over longer periods found that regularly eating a diet high in phytate-containing foods (like wholegrains) can diminish the negative impact that phytates have on mineral absorption (Seth et al., 2015). This means that regularly eating foods high in phytates results in our bodies adapting, and mineral absorption is not negatively impacted by phytates.

In Western and more developed countries, deficiencies in iron, zinc, or other minerals are almost never due to phytate consumption. Zinc and iron deficiencies tend to come from lack of these minerals in our diets, not because uptake of these minerals are blocked. The only evidence I found of phytates interfering with absorption of minerals was in less developed countries, where people may rely on one kind of unrefined grain to provide a majority of their nutrition. Iron deficiencies in these populations are more likely to be due to high quality iron sources being unavailable (Piskin et al, 2022).

I imagine basically everyone that reads this post will not rely on one single type of grain to provide the majority of their daily energy. If you are worried about mineral absorption, it’s generally more useful to think about how to increase the bioavailability of the minerals we eat, rather than start taking things out of your diet. Remember that foods high in phytates are also usually high in fibre which has so many well-researched health benefits. Not that many people reach the daily recommended intake of fibre so I don’t think we should start removing some of the best sources of fibre out of our diets!

If you want to boost your body’s ability to absorb iron, have some food containing Vitamin C (fruits and vegetables are a great source) alongside the food containing iron. You may have heard this before, but Vitamin C helps increase absorption of iron that comes from plant sources. Interestingly, Vitamin C also works to negate the impacts of phytate on iron absorption - it does this by preventing iron from converting into a form that binds very strongly with phytates (Schlemmer et al., 2009). So eating some fruit with your oatmeal can prevent phytates from getting in the way of any mineral absorption your body is trying to do (not that this is something you need to worry about anyway) :)

When I was reading about phytates, I also found some interesting research showing health benefits of phytates. For example, if you or someone you know has PCOS, you may have heard of inositol which is a supplement some people take to help manage their PCOS. Inositol is a phytate! Phytates have also been shown to have some other health benefits, including as an antioxidant, in the prevention of kidney stones and lowering blood glucose levels (Schlemmer et al., 2009).

The final message of this blog post today is a simple one - the people online saying not to eat phytates are just fear mongering! Hopefully I’ve provided some more context over what phytates are and what they do, and eased some fears over whether you suddenly need to avoid any kind of grain or not. It’s difficult, but try not to let the mess of nutrition on social media get to you if you can :)

References

Piskin, E., Cianciosi, D., Gulec, S., Tomas, M. and Capanoglu, E. (2022) ‘Iron Absorption: Factors, Limitations, and Improvement Methods’, ACS Omega, 7(24), pp. 20441 - 20456. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c01833.

Schlemmer, U., Frølich, W., Prieto, R. M. and Grases, F. (2009) ‘Phytate in foods and significance for humans: Food sources, intake, processing, bioavailability, protective role and analysis’, Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 53(S2), pp. S330 - S375. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200900099.

Seth, A., Erick, B., Dan, C., Priscilla, C and Manju, R. (2015) ‘Regular Consumption of a High-Phytate Diet Reduces the Inhibitory Effect of Phytate on Nonheme-Iron Absorption in Women with Suboptimal Iron Stores’, The Journal of Nutrition, 145(8), pp. 1735 - 1739. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.209957.